Hello! My name is Eugene, I am a Python developer. Over the past year and a half, our team began to actively apply the principles of Clean Architecture, moving away from the classic MVC model. And today I will talk about how we came to this, what it gives us, and why the direct transfer of approaches from other PLs is not always a good solution. Python has been my primary development tool for over seven years now. When they ask me what I like most about him, I reply that this is his excellent readability . The first acquaintance began with a reading of the book “Programming a Collective Mind” . I was interested in the algorithms described in it, but all the examples were in a language that was not yet familiar to me then. This was not usual (Python was not yet mainstream in machine learning), listings were often written in pseudo-code or using diagrams. But after a quick introduction to the language, I appreciated its conciseness: everything was easy and clear, nothing superfluous and distracting, only the very essence of the described process. The main merit of this is the amazing design of the language, the very intuitive syntactic sugar. This expressiveness has always been appreciated in the community. What is “ import this ”, necessarily present on the first pages of any textbook: it looks like an invisible overseer, constantly evaluates your actions. On forums, it was worth a beginner to use somehow CamelCase in the variable name in the listing, so immediately the discussion angle shifted towards the idiom of the proposed code with references to PEP8.

Python has been my primary development tool for over seven years now. When they ask me what I like most about him, I reply that this is his excellent readability . The first acquaintance began with a reading of the book “Programming a Collective Mind” . I was interested in the algorithms described in it, but all the examples were in a language that was not yet familiar to me then. This was not usual (Python was not yet mainstream in machine learning), listings were often written in pseudo-code or using diagrams. But after a quick introduction to the language, I appreciated its conciseness: everything was easy and clear, nothing superfluous and distracting, only the very essence of the described process. The main merit of this is the amazing design of the language, the very intuitive syntactic sugar. This expressiveness has always been appreciated in the community. What is “ import this ”, necessarily present on the first pages of any textbook: it looks like an invisible overseer, constantly evaluates your actions. On forums, it was worth a beginner to use somehow CamelCase in the variable name in the listing, so immediately the discussion angle shifted towards the idiom of the proposed code with references to PEP8.The pursuit of elegance plus the powerful dynamism of the language have created many libraries with a truly delightful API.

Nevertheless, Python, although powerful, is just a tool that allows you to write expressive, self-documenting code, but it does not guarantee this , nor does PEP8 compliance. When our seemingly simple online store on Django begins to make money and, as a result, pump up features, at one point we understand that it is not so simple, and even making basic changes requires more and more effort, and most importantly, this trend is growing. What happened and when everything went wrong?Bad code

Bad code is not one that does not follow PEP8 or does not meet the requirements of cyclomatic complexity. Bad code is, first of all, uncontrolled dependencies , which lead to the fact that a change in one place of the program leads to unpredictable changes in other parts. We are losing control over the code; expanding the functionality requires a detailed study of the project. Such code loses its flexibility and, as it were, resists making changes, while the program itself becomes “fragile”. Clean architecture

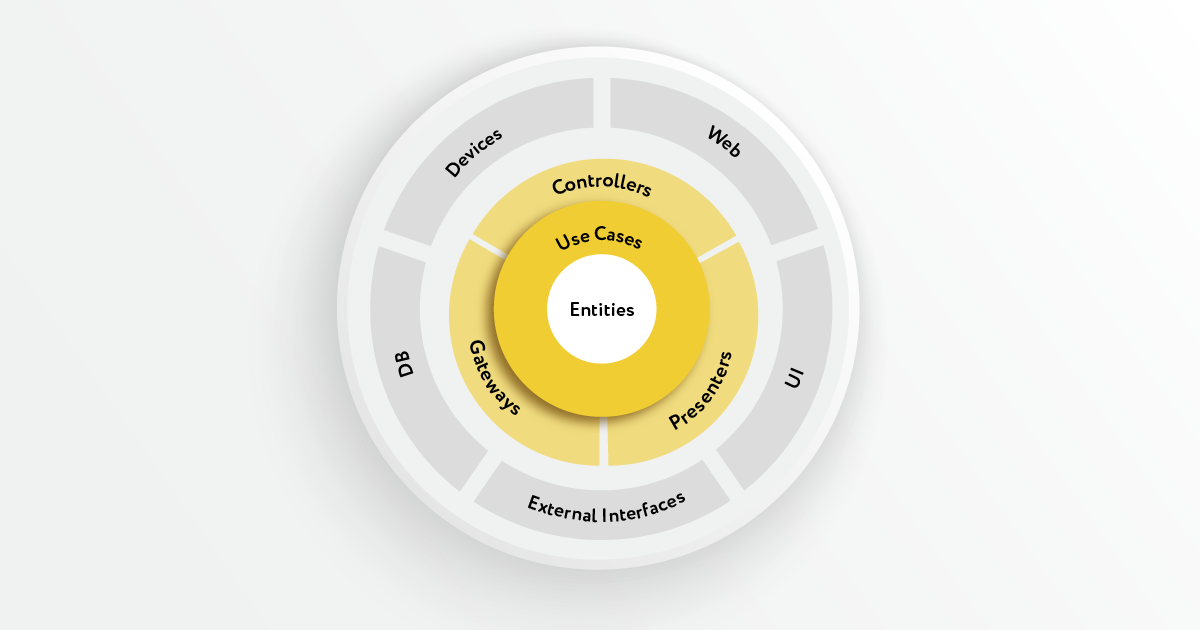

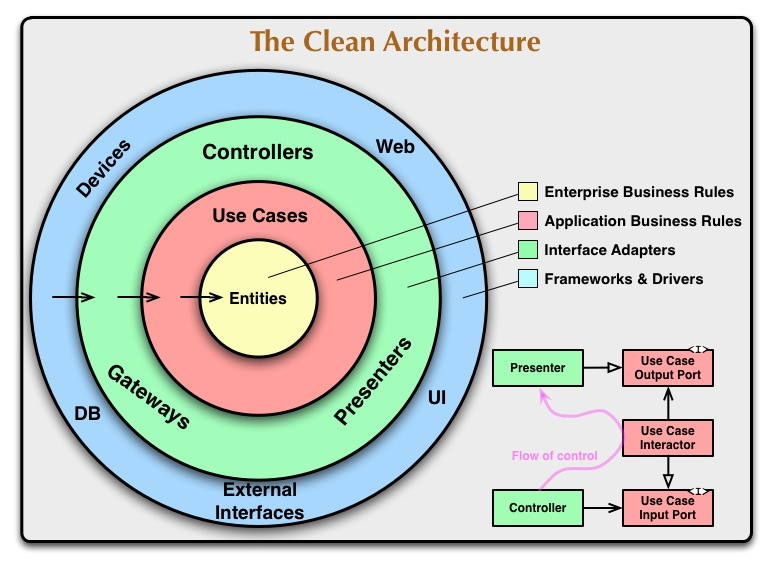

The chosen architecture of the application should avoid this problem, and we are not the first to encounter this: there has been a discussion in the Java community about creating an optimal application design for a long time.Back in 2000, Robert Martin (also known as Uncle Bob) in his article “ Design and Design Principles ” brought together five principles for designing OOP applications under the memorable acronym SOLID. These principles have been well received by the community and have gone far beyond the Java ecosystem. Nevertheless, they are very abstract in nature. Later there were several attempts to develop a general application design based on SOLID principles. These include: “Hexagonal architecture”, “Ports and adapters”, “Bulbous architecture” and they all have much in common, albeit different implementation details. And in 2012, an article was published by the same Robert Martin, where he proposed his own version called “ Clean Architecture ”. According to Uncle Bob, architecture is primarily “ borders and barriers ”, it is necessary to clearly understand the needs and limit software interfaces in order not to lose control over the application. To do this, the program is divided into layers. Turning from one layer to another, only data can be transferred (simple structures and DTO objects can act as data ) - this is the rule of boundaries. Another most frequently quoted phrase that “the application should scream ” means that the main thing in the application is not the used framework or data storage technology, but what this application actually does, what function it performs - the business logic of the application . Therefore, the layers do not have a linear structure, but have a hierarchy . Hence two more rules:

According to Uncle Bob, architecture is primarily “ borders and barriers ”, it is necessary to clearly understand the needs and limit software interfaces in order not to lose control over the application. To do this, the program is divided into layers. Turning from one layer to another, only data can be transferred (simple structures and DTO objects can act as data ) - this is the rule of boundaries. Another most frequently quoted phrase that “the application should scream ” means that the main thing in the application is not the used framework or data storage technology, but what this application actually does, what function it performs - the business logic of the application . Therefore, the layers do not have a linear structure, but have a hierarchy . Hence two more rules:- The priority rule for the inner layer - it is the inner layer that determines the interface through which it will interact with the outside world;

- Dependency rule - Dependencies should be directed from the inner layer to the outer.

The last rule is quite atypical in the Python world. To apply any complicated business logic scenario, you always need to access external services (for example, a database), but to avoid this dependency, the business logic layer must itself declare the interface by which it will interact with the outside world. This technique is called “ dependency inversion ” (the letter D in SOLID) and is widely used in languages with static typing. According to Robert Martin, this is the main advantage that came with the OOP .These three rules are the essence of Clean Architecture:- Border crossing rule;

- Dependency rule;

- The priority rule of the inner layer.

The advantages of this approach include:- Ease of testing - the layers are isolated, respectively, they can be tested without monkey-patching, you can granularly set the coating for different layers, depending on the degree of their importance;

- The simplicity of changing business rules , since they are all collected in one place, are not spread over the project and are not mixed with low-level code;

- Independence from external agents : the presence of abstractions between business logic and the outside world in certain cases allows you to change external sources without affecting the internal layers. It works if you have not tied the business logic to the specific features of external agents, for example, database transactions;

- , , , .

, . . , . « Clean Architecture».

Python

This is a theory, examples of practical application can be found in the original article, reports and book of Robert Martin. They rely on several common design patterns from the Java world: Adapter, Gateway, Interactor, Fasade, Repository, DTO , etc.Well, what about Python? As I said, laconicism is valued in the Python community. What has taken root in others is far from the fact that it will take root with us. The first time I turned to this topic three years ago, then there were not many materials on the topic of using Clean Architecture in Python, but the first link in Google was the Leonardo Giordani project : the author describes in detail the process of creating an API for a site for searching for real estate using the TDD method, applying Clean Architecture.Unfortunately, despite the scrupulous explanation and following all the canons of Uncle Bob, this example is rather scary . The project API consists of one method - getting a list with an available filter. I think that even for a novice developer, the code for such a project will take no more than 15 lines. But in this case, he took six packets. You can refer to a not entirely successful layout, and this is true, but in any case, it is difficult for someone to explain the effectiveness of this approach , referring to this project.There is a more serious problem, if you do not read the article and immediately begin to study the project, then it is quite difficult to understand. Consider the implementation of business logic:from rentomatic.response_objects import response_objects as res

class RoomListUseCase(object):

def __init__(self, repo):

self.repo = repo

def execute(self, request_object):

if not request_object:

return res.ResponseFailure.build_from_invalid_request_object(

request_object)

try:

rooms = self.repo.list(filters=request_object.filters)

return res.ResponseSuccess(rooms)

except Exception as exc:

return res.ResponseFailure.build_system_error(

"{}: {}".format(exc.__class__.__name__, "{}".format(exc)))

The RoomListUseCase class that implements business logic (not very similar to business logic, right?) Of the project is initialized by the repo object . But what is a repo ? Of course, from the context, we can understand that repo implements the Repository template for accessing data, if we look at the body of RoomListUseCase, we understand that it must have one list method, the input of which is a list of filters, which is not clear at the output, you need to look in ResponseSuccess. And if the scenario is more complex, with multiple access to the data source? It turns out to understand what repo is, you can only refer to the implementation. But where is she located? It lies in a separate module, which is in no way associated with RoomListUseCase. Thus, to understand what is happening, you need to go up to the upper level (the level of the framework) and see what is fed to the input of the class when creating the object.You might think that I list the disadvantages of dynamic typing, but this is not entirely true. It is dynamic typing that allows you to write expressive and compact code . The analogy with microservices comes to mind, when we cut a monolith into microservices, the design takes on additional rigidity, since anything can be done inside the microservice (PL, frameworks, architecture), but it must comply with the declared interface. So here: when we divided our project into layers,The relationships between the layers must be consistent with the contract , while inside the layer, the contract is optional. Otherwise, you need to keep a fairly large context in your head. Remember, I said that the problem with bad code is dependencies, and so, without an explicit interface, we again slide back to where we wanted to get away - to the absence of obvious cause-effect relationships .repo RoomListUseCase, execute — . - , , . - . , , , repo .

In general, at that time I abandoned Clean Architecture in a new project, again applying the classic MVC. But, having filled the next batch of cones, he returned to this idea a year later, when, at last, we began to launch services in Python 3.5+. As you know, he brought type annotations and data classes: Two powerful interface description tools. Based on them, I sketched a prototype of the service, and the result was already much better: the layers stopped scattering, despite the fact that there was still a lot of code, especially when integrating with the framework. But that was enough to start applying this approach in small projects. Gradually, frameworks began to appear that focused on the maximum use of type annotations: apistar (now starlette), moltenframework. The pydantic / FastAPI bundle is now common, and integration with such frameworks has become much easier. This is what the above example of restomatic / services.py would look like:from typing import Optional, List

from pydantic import BaseModel

class Room(BaseModel):

code: str

size: int

price: int

latitude: float

longitude: float

class RoomFilter(BaseModel):

code: Optional[str] = None

price_min: Optional[int] = None

price_max: Optional[int] = None

class RoomStorage:

def get_rooms(self, filters: RoomFilter) -> List[Room]: ...

class RoomListUseCase:

def __init__(self, repo: RoomStorage):

self.repo = repo

def show_rooms(self, filters: RoomFilter) -> List[Room]:

rooms = self.repo.get_rooms(filters=filters)

return rooms

RoomListUseCase - a class that implements the business logic of the project. You should not pay attention to the fact that all that the show_rooms method does is call to RoomStorage (I did not come up with this example). In real life, there can also be a discount calculation, ranking a list based on advertisements, etc. However, the module is self-sufficient. If we want to use this scenario in another project, we will have to implement RoomStorage. And what is needed for this is clearly visible right from the module. Unlike the previous example, such a layer is self-sufficient , and when changing it is not necessary to keep the whole context in mind. From non-systemic dependencies only pydantic, why, it will become clear in the plug-in of the framework. No dependencies, another way to improve code readability, not additional context, even a novice developer will be able to understand what this module does.A business logic scenario does not have to be a class; below is an example of a similar scenario in the form of a function:def rool_list_use_case(filters: RoomFilter, repo: RoomStorage) -> List[Room]:

rooms = repo.get_rooms(filters=filters)

return rooms

And here is the connection to the framework:from typing import List

from fastapi import FastAPI, Depends

from rentomatic import services, adapters

app = FastAPI()

def get_use_case() -> services.RoomListUseCase:

return services.RoomListUseCase(adapters.MemoryStorage())

@app.post("/rooms", response_model=List[services.Room])

def rooms(filters: services.RoomFilter, use_case=Depends(get_use_case)):

return use_case.show_rooms(filters)

Using the get_use_case function, FastAPI implements the Dependency Injection pattern . We do not need to worry about data serialization, all the work is done by FastAPI in conjunction with pydantic. Unfortunately, data are not always business logic format suitable for live broadcast in the restaurant <and, on the contrary, the business logic does not know where the data came - with slashes, request body, cookies, etc . In this case, the body of the room function will have a certain conversion of input and output data, but in most cases, if we work with the API, such an easy proxy function is enough. , , , RoomStorage. , 15 , , , .

I intentionally did not separate the layer of business logic, as the canonical Clean Architecture model suggests. The Room class was supposed to be in the Entity domain region layer representing the domain region, but for this example there is no need for this. From combining Entity and UseCase layers, the project does not cease to be a Clean Architecture implementation. Robert Martin himself has repeatedly said that the number of layers can vary both upward and downward. At the same time, the project meets the main criteria of Clean Architecture:- Border crossing rule : pydantic models, which are essentially DTOs, cross borders ;

- Dependency rule : the business logic layer is independent of other layers;

- The priority rule for the inner layer : it is the business logic layer that defines the interface (RoomStorage), through which the business logic interacts with the outside world.

Today, several projects of our team, implemented using the described approach, are working on the prod. I try to organize even the smallest services this way. It trains well - questions that I hadn’t thought about before come up. For example, what is business logic here? This is far from always obvious, for example, if you are writing some kind of proxy. Another important point is to learn to think differently.. When we get a task, we usually start thinking about the frameworks, the services used, about whether there will be a need for a queue where it is better to store this data, which can be cached. In the approach dictating Clean Architecture, we must first implement the business logic and only then move on to implementing interaction with the infrastructure, since, according to Robert Martin, the main task of architecture is to delay the moment when the connection with any The infrastructure layer will be an integral part of your application.In general, I see a favorable prospect for using Clean Architecture in Python. But the form, most likely, will be significantly different from how it is accepted in other PLs. Over the past few years, I have seen a significant increase in interest in the topic of architecture in the community. So, at the last PyCon there were several reports on the use of DDD, and the guys from dry-labs should be noted separately . In our company, many teams are already implementing the approach described to one degree or another. We are all doing the same thing, we have grown, our projects have grown, the Python community has to work with this, define the common style and language that, for example, once became for all Django.