Hello, Habr! I present to you the translation of the article Functional options on steroids by Márk Sági-Kazár . Functional options are Go's paradigm for clean and extensible APIs. She is popularized by Dave Cheney and Rob Pike . This post is about practices that have been around the template since it was first introduced.Functional options have emerged as a way to create good and clean APIs with a configuration that includes optional parameters. There are many obvious ways to do this (constructor, configuration structure, setters, etc.), but when you need to pass dozens of options, they are poorly read and do not give such good APIs as functional options.

Functional options are Go's paradigm for clean and extensible APIs. She is popularized by Dave Cheney and Rob Pike . This post is about practices that have been around the template since it was first introduced.Functional options have emerged as a way to create good and clean APIs with a configuration that includes optional parameters. There are many obvious ways to do this (constructor, configuration structure, setters, etc.), but when you need to pass dozens of options, they are poorly read and do not give such good APIs as functional options.Introduction - what are functional options?

Usually, when you create an “object”, you call the constructor with the necessary arguments:obj := New(arg1, arg2)

(Let's ignore the fact that there are no traditional constructors in Go.)Functional options allow you to extend the API with additional parameters, turning the above line into the following:

obj := New(arg1, arg2)

obj := New(arg1, arg2, myOption1, myOption2)

Functional options are basically arguments of a variable function that takes as parameters a composite or intermediate configuration type. Due to its variable nature, it is perfectly acceptable to call the constructor without any options, keeping it clean, even if you want to use the default values.To better demonstrate the pattern, let's take a look at a realistic example (without functional options):type Server struct {

addr string

}

func NewServer(addr string) *Server {

return &Server {

addr: addr,

}

}

After adding the timeout option, the code looks like this:type Server struct {

addr string

timeout time.Duration

}

func Timeout(timeout time.Duration) func(*Server) {

return func(s *Server) {

s.timeout = timeout

}

}

func NewServer(addr string, opts ...func(*Server)) *Server {

server := &Server {

addr: addr,

}

for _, opt := range opts {

opt(server)

}

return server

}

The resulting API is easy to use and easy to read:

server := NewServer(":8080")

server := NewServer(":8080", Timeout(10 * time.Second))

server := NewServer(":8080", Timeout(10 * time.Second), TLS(&TLSConfig{}))

For comparison, here is what initialization looks like using the constructor and using the config configuration structure:

server := NewServer(":8080")

server := NewServerWithTimeout(":8080", 10 * time.Second)

server := NewServerWithTimeoutAndTLS(":8080", 10 * time.Second, &TLSConfig{})

server := NewServer(":8080", Config{})

server := NewServer(":8080", Config{ Timeout: 10 * time.Second })

server := NewServer(":8080", Config{ Timeout: 10 * time.Second, TLS: &TLSConfig{} })

The advantage of using functional options over the constructor is probably obvious: they are easier to maintain and read / write. Functional parameters also exceed the configuration structure when parameters are not passed to the constructor. In the following sections I will show even more examples where the configuration structure may not live up to expectations.Read the full history of functional options by clicking on the links in the introduction. (translator's note - a blog with an original article by Dave Cheney is not always available in Russia and you may need to connect via VPN to view it. Also, information from the article is available in the video of his report on dotGo 2014 )Functional Options Practices

Functional options themselves are nothing more than functions passed to the constructor. Ease of use of simple functions gives flexibility and has great potential. Therefore, it is not surprising that over the years a lot of practices have appeared around the template. Below I will provide a list of what I consider the most popular and useful practices.Email me if you think something is missing.Type of options

The first thing you can do when applying the functional options template is to determine the type for the optional function:

type Option func(s *Server)

Although this may not seem like a big improvement, the code becomes more readable by using a type name instead of defining a function:func Timeout(timeout time.Duration) func(*Server) { }

func NewServer(addr string, opts ...func(s *Server)) *Server

func Timeout(timeout time.Duration) Option { }

func NewServer(addr string, opts ...Option) *Server

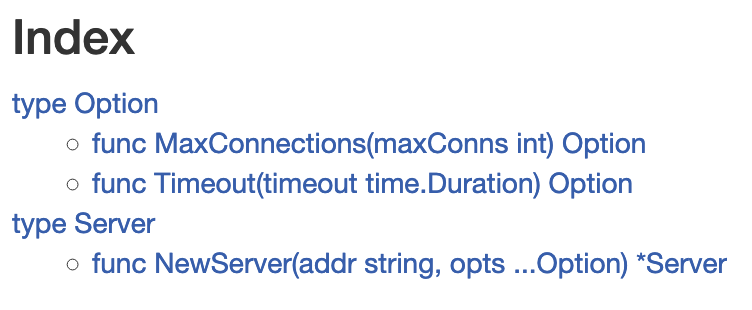

Another advantage of having an option type is that Godoc places option functions under the type:

Option Type List

Typically, functional parameters are used to create a single instance of something, but this is not always the case. Reusing the default parameter list when creating multiple instances is also not uncommon:defaultOptions := []Option{Timeout(5 * time.Second)}

server1 := NewServer(":8080", append(defaultOptions, MaxConnections(10))...)

server2 := NewServer(":8080", append(defaultOptions, RateLimit(10, time.Minute))...)

server3 := NewServer(":8080", append(defaultOptions, Timeout(10 * time.Second))...)

This is not very readable code, especially considering that the point of using functional options is to create friendly APIs. Fortunately, there is a way to simplify this. We just need to slice the [] Option directly with the option:

func Options(opts ...Option) Option {

return func(s *Server) {

for _, opt := range opts {

opt(s)

}

}

}

After replacing the slice with the Options function, the above code becomes:defaultOptions := Options(Timeout(5 * time.Second))

server1 := NewServer(":8080", defaultOptions, MaxConnections(10))

server2 := NewServer(":8080", defaultOptions, RateLimit(10, time.Minute))

server3 := NewServer(":8080", defaultOptions, Timeout(10 * time.Second))

Prefixes of the With / Set Options

Options are often complex types, unlike a timeout or maximum number of connections. For example, in the server package, you can define the Logger interface as an option (and use it if there is no default logger):type Logger interface {

Info(msg string)

Error(msg string)

}

Obviously, the Logger name cannot be used as the option name, as it is already used by the interface. You can call the option LoggerOption, but it's not a very friendly name. If you look at the constructor as a sentence, in our case the word with: WithLogger comes to mind.func WithLogger(logger Logger) Option {

return func(s *Server) {

s.logger = logger

}

}

NewServer(":8080", WithLogger(logger))

Another common example of a complex type option is a slice of values:type Server struct {

whitelistIPs []string

}

func WithWhitelistedIP(ip string) Option {

return func(s *Server) {

s.whitelistIPs = append(s.whitelistIPs, ip)

}

}

NewServer(":8080", WithWhitelistedIP("10.0.0.0/8"), WithWhitelistedIP("172.16.0.0/12"))

In this case, the option usually appends the values to existing ones, rather than overwriting them. If you need to overwrite an existing set of values, you can use the word set in the option name:func SetWhitelistedIP(ip string) Option {

return func(s *Server) {

s.whitelistIPs = []string{ip}

}

}

NewServer(

":8080",

WithWhitelistedIP("10.0.0.0/8"),

WithWhitelistedIP("172.16.0.0/12"),

SetWhitelistedIP("192.168.0.0/16"),

)

Preset Template

Special use cases are usually universal enough to support them in the library. In the case of a configuration, this may mean a set of parameters grouped together and used as a preset for use. In our example, the Server can have open and internal usage scenarios that set timeouts, speed limits, number of connections, etc. in different ways.

func PublicPreset() Option {

return Options(

WithTimeout(10 * time.Second),

MaxConnections(10),

)

}

func InternalPreset() Option {

return Options(

WithTimeout(20 * time.Second),

WithWhitelistedIP("10.0.0.0/8"),

)

}

Although presets may be useful in some cases, they are probably of great value in internal libraries, and in public libraries their value is less.Default Type Values vs Default Preset Values

Go always has default values. For numbers, this is usually zero, for Boolean types, it is false, and so on. In an optional configuration, it is considered good practice to rely on the default values. For example, a null value should mean an unlimited timeout instead of its absence (which is usually meaningless).In some cases, the default type value is not a good default value. For example, the default value for Logger is nil, which can lead to panic (if you do not protect the logger calls with conditional checks).In these cases, setting the value in the constructor (before applying the parameters) is a good way to determine the fallback:func NewServer(addr string, opts ...func(*Server)) *Server {

server := &Server {

addr: addr,

logger: noopLogger{},

}

for _, opt := range opts {

opt(server)

}

return server

}

I saw examples with default presets (using the template described in the previous section). However, I do not consider this a good practice. This is much less expressive than just setting default values in the constructor:func NewServer(addr string, opts ...func(*Server)) *Server {

server := &Server {

addr: addr,

}

opts = append([]Option{DefaultPreset()}, opts...)

for _, opt := range opts {

opt(server)

}

return server

}

Configuration structure option

Having a Config structure as a functional option is probably not as common, but this is sometimes found. The idea is that the functional options refer to the configuration structure instead of referring to the actual object being created:type Config struct {

Timeout time.Duration

}

type Option func(c *Config)

type Server struct {

config Config

}

This template is useful when you have many options, and creating a configuration structure seems cleaner than listing all the options in a function call:config := Config{

Timeout: 10 * time.Second

}

NewServer(":8080", WithConfig(config))

Another use case for this template is to set default values:config := Config{

Timeout: 10 * time.Second

}

NewServer(":8080", WithConfig(config), WithTimeout(20 * time.Second))

Advanced Templates

After writing dozens of functional options, you may wonder if there is a better way to do this. Not in terms of use, but in terms of long-term support.For example, what if we could define types and use them as parameters:type Timeout time.Duration

NewServer(":8080", Timeout(time.Minute))

(Note that the use of the API remains the same)It turns out that by changing the Option type, we can easily do this:

type Option interface {

apply(s *Server)

}

Overriding an optional function as an interface opens the door for a number of new ways to implement functional options:Various built-in types can be used as parameters without a wrapper function:

type Timeout time.Duration

func (t Timeout) apply(s *Server) {

s.timeout = time.Duration(t)

}

Lists of options and configuration structures (see previous sections) can also be redefined as follows:

type Options []Option

func (o Options) apply(s *Server) {

for _, opt := range o {

o.apply(s)

}

}

type Config struct {

Timeout time.Duration

}

func (c Config) apply(s *Server) {

s.config = c

}

My personal favorite is the ability to reuse the option in multiple constructors:

type ServerOption interface {

applyServer(s *Server)

}

type ClientOption interface {

applyClient(c *Client)

}

type Option interface {

ServerOption

ClientOption

}

func WithLogger(logger Logger) Option {

return withLogger{logger}

}

type withLogger struct {

logger Logger

}

func (o withLogger) applyServer(s *Server) {

s.logger = o.logger

}

func (o withLogger) applyClient(c *Client) {

c.logger = o.logger

}

NewServer(":8080", WithLogger(logger))

NewClient("http://localhost:8080", WithLogger(logger))

Summary

Functional parameters is a powerful template for creating clean and extensible APIs with dozens of parameters. Although this does a little more work than supporting a simple configuration structure, it provides much more flexibility and provides much cleaner APIs than alternatives.