How level designers use architecture theory to create game levels

The theory of architecture includes many aspects and is inherently an alloy of numerous artistic, social and psychological techniques. However, regardless of the architectural movement or era, one idea always remains unchanged: architecture is a reasonable way to organize space.Despite the fact that levels in video games are intangible, players interact with game spaces in the same way that their physical bodies interact with the outside world. So, an architectural approach can also be applied to level design.In this article, we will look at how level designers use the theory of architecture in their field. First, we will analyze in theory several principles for constructing an architectural space, and then consider real-life examples. Thus, we not only learn the ways in which level designers use, destroy or in any other way rethink the theory of architecture to fit their needs, but also see how the genre of the game affects their decisions.

The theory of architecture includes many aspects and is inherently an alloy of numerous artistic, social and psychological techniques. However, regardless of the architectural movement or era, one idea always remains unchanged: architecture is a reasonable way to organize space.Despite the fact that levels in video games are intangible, players interact with game spaces in the same way that their physical bodies interact with the outside world. So, an architectural approach can also be applied to level design.In this article, we will look at how level designers use the theory of architecture in their field. First, we will analyze in theory several principles for constructing an architectural space, and then consider real-life examples. Thus, we not only learn the ways in which level designers use, destroy or in any other way rethink the theory of architecture to fit their needs, but also see how the genre of the game affects their decisions.Emotionally Oriented Space Planning

Parti pris, or parti, is a design method that some architects use in the early stages of planning to determine the spatial parameters of their project. Being a schematic interpretation, a kind of starting point of the whole project, parti can be supplemented by external ideas, which often go beyond the physical form of the object. Thus, an architectural object can become a physical embodiment of a certain philosophical concept, if such was laid in its foundation. Figure 1. Example parti: project of the Mining Center for the Faculty of Engineering of the Catholic Faculty (Santiago, Chile)The Roman concept of genius loci, or “the spirit of a place”, also has a direct relation to architecture: it says that every place has not only certain physical parameters, but also its own character. In the case of level design, the spirit of the place can be created through the prism of some supposed experience already gained by the player. So, in the chapter “Deja Vu on Ishimur” of the Dead Space 2 horror, the player again finds himself at the start of the first part of the game and in his flashbacks passes through its most memorable moments. The spirit of the place here can be seen as a way of enhancing the dramatic tension in the entire spatial volume of the level.

Figure 1. Example parti: project of the Mining Center for the Faculty of Engineering of the Catholic Faculty (Santiago, Chile)The Roman concept of genius loci, or “the spirit of a place”, also has a direct relation to architecture: it says that every place has not only certain physical parameters, but also its own character. In the case of level design, the spirit of the place can be created through the prism of some supposed experience already gained by the player. So, in the chapter “Deja Vu on Ishimur” of the Dead Space 2 horror, the player again finds himself at the start of the first part of the game and in his flashbacks passes through its most memorable moments. The spirit of the place here can be seen as a way of enhancing the dramatic tension in the entire spatial volume of the level.The principle of "figure-background"

So, both architects and level designers should have a deep understanding of how to organize forms and spaces. In this, Gestalt psychology comes to their aid - a theory that studies the human perception of the visual world.Level designer Christopher Totten calls level design “the art of contrasts”, to which the principle of the background figure can be applied - one of the components of the Gestalt theory. According to this principle, all objects in a person’s field of vision can be divided into two contrasting types of elements: figures and background.According to Gestalt psychologist Kurt Koffka, "the whole is nothing but the sum of its parts." This idea is presented to them through the prism of architectural design: equal attention must be paid to form and space so that they are distinguishable and correctly interpreted. Architect Francis Ching defines the relationship between the figure and the background as “the unity of opposites,” thereby indicating that both components are equally important for visual composition.There are two ways to place shapes in space, which determine how the surrounding background will be visually perceived:- Positive space is formed when the figures are arranged so that between them there is still some form. The background itself in this case can also be perceived as a separate figure.

- , , .

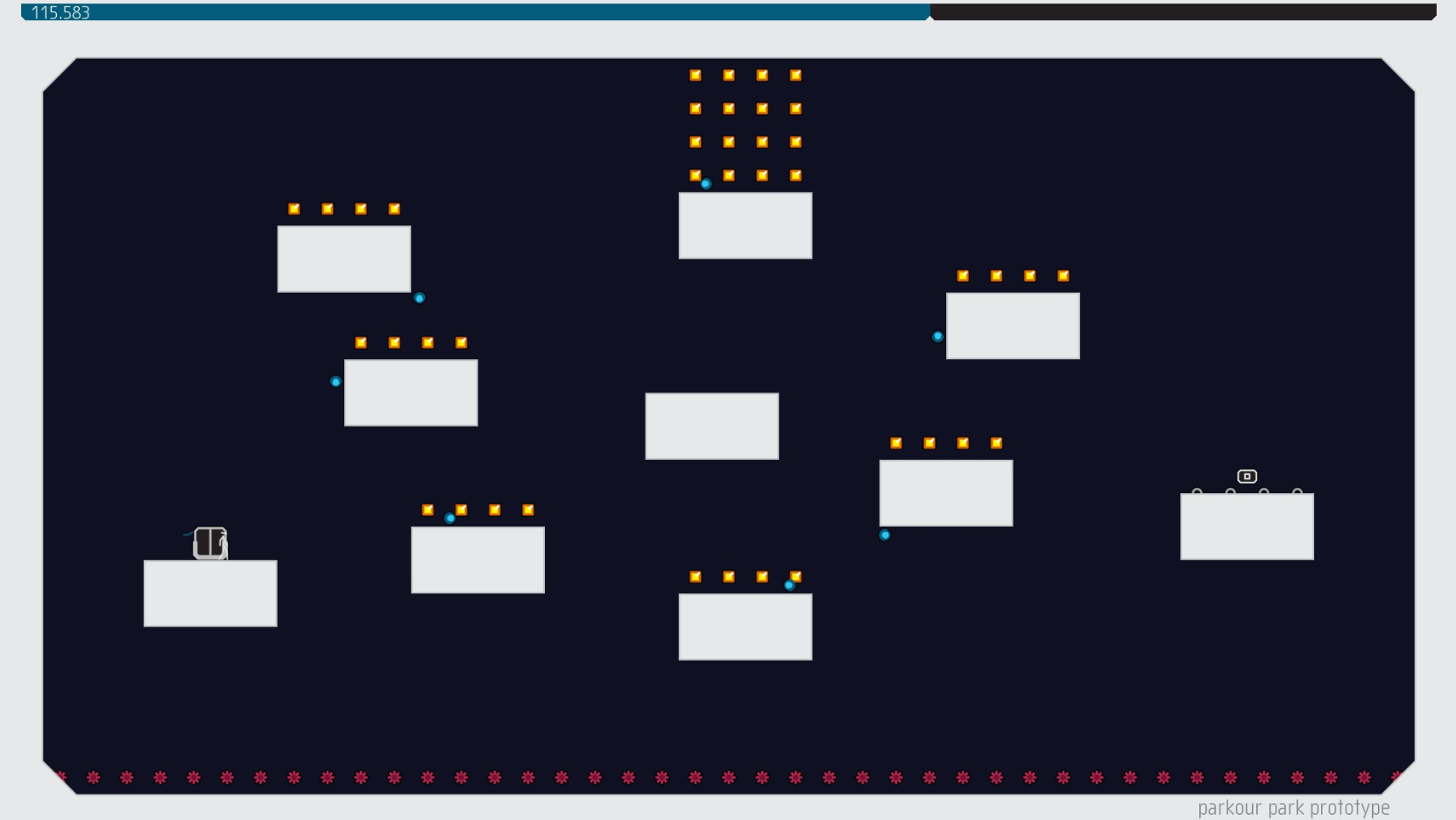

In other words, in architecture, a positive space equals a built-up space, and negative space equals an undeveloped space.The principles underlying the “figure-background” theory, as applied to architecture, are also transformed into a different formulation: "an architectural form arises at the junction between mass and void." This statement is reflected in all applications of spatial theory both in architecture and in level design. Here, mass and void are the material equivalents of a figure and background, and in order to maintain visual clarity, there must always be a tangible contrast between form and space.The contrast between a figure and a background has many ways to achieve it. Among them are color, volume and texture.Being a two-dimensional platformer, N ++ cannot take into account all possible architectural aspects. But despite this, the minimalistic design of the game levels emphasizes the symbiotic dichotomy between the mass and the void: the figures and background here are easily distinguishable from each other thanks to contrasting colors. Figure 2. N ++ (2016), Parkour Park Prototype levelHere, the white rectangles act as physical objects, and the dark blue void around is the space in which the players move. Correctly selected location of obstacles and opponents in the playing space helps prevent the player from misunderstanding what is on the screen a figure and what is a background. Such a problem can occur when both elements of the visual composition have an approximately equal ratio.Some levels in N ++ really suffer from this: their physical masses and empty spaces occupy visually the same amount of space and thereby violate the distinction between shapes and backgrounds. This situation may be aggravated if the level masses seem to be visual extensions of the game edging. An example of this is the Learning Process layer.Having a minimalistic color palette, such scenarios can potentially confuse the player, because in this way the game environment becomes more difficult to read. On the other hand, such abstract visual compositions can be attributed to a distinctive style of play that creates a peculiar spirit of the place.

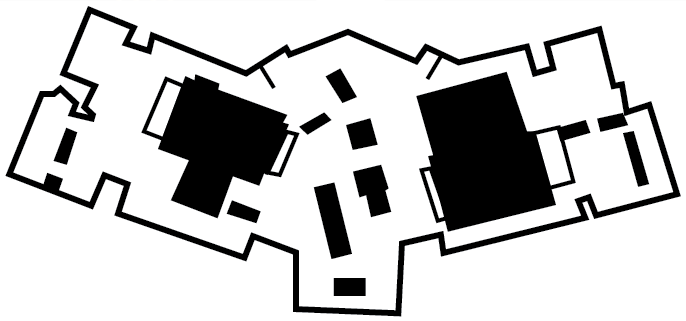

Figure 2. N ++ (2016), Parkour Park Prototype levelHere, the white rectangles act as physical objects, and the dark blue void around is the space in which the players move. Correctly selected location of obstacles and opponents in the playing space helps prevent the player from misunderstanding what is on the screen a figure and what is a background. Such a problem can occur when both elements of the visual composition have an approximately equal ratio.Some levels in N ++ really suffer from this: their physical masses and empty spaces occupy visually the same amount of space and thereby violate the distinction between shapes and backgrounds. This situation may be aggravated if the level masses seem to be visual extensions of the game edging. An example of this is the Learning Process layer.Having a minimalistic color palette, such scenarios can potentially confuse the player, because in this way the game environment becomes more difficult to read. On the other hand, such abstract visual compositions can be attributed to a distinctive style of play that creates a peculiar spirit of the place. Figure 3. N ++ (2016), Learning Process layer

Figure 3. N ++ (2016), Learning Process layerLandmarks

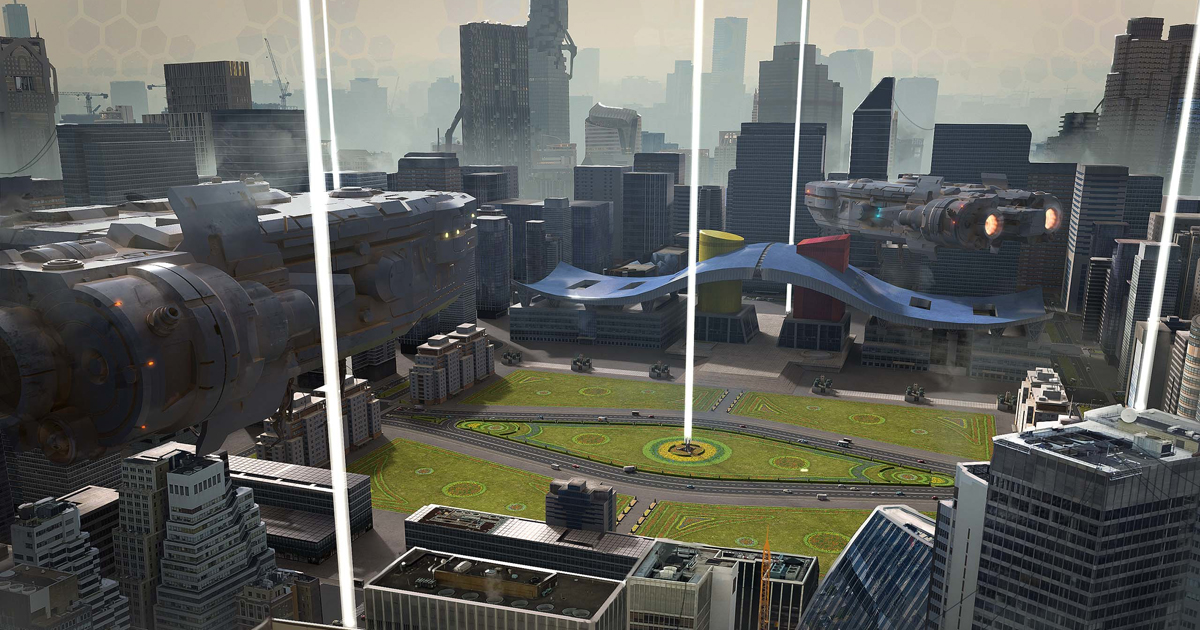

Kevin Lynch, a well-known American urban planner, suggested in his book The Image of the City that the urban environment consists of five key forms: paths, borders, districts, nodes, and landmarks. One of these elements - a landmark, or landmark - can be considered an important tool in level design. On an urban scale, landmarks are usually physical structures such as towers, buildings or statues that stand out against the background and serve as spatial anchors that reliably indicate the direction when moving. In addition, for the most part being bright and memorable buildings, landmarks can contribute to the spirit of the city’s place.Lynch believed that the main factor for an object to be its reference point is its visual contrast with the background, which can be achieved using the principle of the background shape. The Eiffel Tower is perhaps one of the most famous examples, effectively using this principle. Here the sky is the very background on which the figure is placed. The Eiffel Tower is a huge landmark for Paris, which can be observed at a distance of several kilometers from its location. Figure 4. The Eiffel Tower. Architect: Gustave Eiffel, 1889Naturally, to achieve a similar effect, level designers can use skyboxes. Skybox can be set up so that it is visually distinguishable from the horizon of the game, as a result of which a huge amount of negative space will be used as a background for landmarks.In the MMORPG “World of Warcraft: Battle for Azeroth”, arriving in the fictional city of Dazar'alor, players see a monolithic structure: it is a gilded pyramid that resembles similar buildings in Central America. In this pyramid are the highest echelons of local society and the top of power. Visually, the pyramid contrasts with the sky background in the same way as real-life attractions like the Eiffel Tower do.

Figure 4. The Eiffel Tower. Architect: Gustave Eiffel, 1889Naturally, to achieve a similar effect, level designers can use skyboxes. Skybox can be set up so that it is visually distinguishable from the horizon of the game, as a result of which a huge amount of negative space will be used as a background for landmarks.In the MMORPG “World of Warcraft: Battle for Azeroth”, arriving in the fictional city of Dazar'alor, players see a monolithic structure: it is a gilded pyramid that resembles similar buildings in Central America. In this pyramid are the highest echelons of local society and the top of power. Visually, the pyramid contrasts with the sky background in the same way as real-life attractions like the Eiffel Tower do. Figure 5. World of Warcraft: Battle of Azeroth (2018). Dazar'alor Pyramid Thelocation of the Dazar'alor Pyramid follows the architectural rules for spatial elevation. Thus, the physical elevation of a figure over a general relief is often a culturally justified decision, since it speaks of the religious or social significance of the object for the area over which it is visible. The pyramid is one of the highest places on the entire Zandalar continent, which indicates its importance for the cultural identity of the city. Its location in the middle of the homeland of the Zandalari trolls symbolizes the dominance of the race over the adjacent land. This idea is also continued in the bold triangular shape of the structure, imitating the surrounding mountains.In the same way, the Citadel in Half-Life 2 dominates the surrounding landscape, but makes it so that its peak lost in the clouds seems overwhelmingly depressing. The futuristic muted outlines and monstrous dimensions of the Citadel give it a contradictory but contrasting appearance compared to the old brick houses of City 17. It causes a feeling of fear and anxiety, which, according to Totten, is quite appropriate, because in this way the game immediately means that the Citadel is the place habitat of the main antagonist of the game.

Figure 5. World of Warcraft: Battle of Azeroth (2018). Dazar'alor Pyramid Thelocation of the Dazar'alor Pyramid follows the architectural rules for spatial elevation. Thus, the physical elevation of a figure over a general relief is often a culturally justified decision, since it speaks of the religious or social significance of the object for the area over which it is visible. The pyramid is one of the highest places on the entire Zandalar continent, which indicates its importance for the cultural identity of the city. Its location in the middle of the homeland of the Zandalari trolls symbolizes the dominance of the race over the adjacent land. This idea is also continued in the bold triangular shape of the structure, imitating the surrounding mountains.In the same way, the Citadel in Half-Life 2 dominates the surrounding landscape, but makes it so that its peak lost in the clouds seems overwhelmingly depressing. The futuristic muted outlines and monstrous dimensions of the Citadel give it a contradictory but contrasting appearance compared to the old brick houses of City 17. It causes a feeling of fear and anxiety, which, according to Totten, is quite appropriate, because in this way the game immediately means that the Citadel is the place habitat of the main antagonist of the game. Figure 6. Half-Life 2 (2004). Citadel City 17

Figure 6. Half-Life 2 (2004). Citadel City 17Using landmarks as road signs

Among other things, level designers can use landmarks as physical goals or places that the player needs to achieve. The effect of using such waypoints can be enhanced by an architectural technique called denial and reward. Its purpose is to get the most satisfaction from arriving at a landmark or other destination.In the context of level design, the “refusal and reward” technique is used in the process of following a player for a landmark. Sometimes a landmark temporarily disappears from the field of view, and then is shown from a different distance or angle. Finding a landmark closer and closer can indicate the course of time for the player in a natural and unobtrusive way, forcing him to continue on his way.During the journey, this technique performs best. Suppose the main goal of the game is to reach a mountain, a distant landmark, which is introduced into the narrative from the very beginning. The mountain often disappears from view when the player performs third-party tasks and crosses an abandoned area, but then reappears - and each time it gets closer to the player. As you approach it, the observer becomes available more and more visual details: among them are weather changes or fragments of ruins that were impossible to see from a greater distance.Positive spaces in an urban environment

In an urban environment, architectural figures are often placed in such a way that they form additional spaces within themselves. These positive spaces act as “public spaces” in which people interact. On the map of Nolly below you can observe such spaces located throughout Rome. Figure 7. A fragment of the Nolly map (1748)Major cities in World of Warcraft are social media that share the same positive space features. As in many real cities, positive spaces in Stormwind are formed through the rational placement of architectural figures. On the map of Stormwind it can be seen that the city has its own areas that differ from each other in the color of the roof. This is the basic and easiest way to reflect the visual identity of this another of the five Lynch forms. In addition, for more clear and visual division of space into areas in Stormwind, there are water channels, thanks to which the transition from one area to another becomes more obvious for players.

Figure 7. A fragment of the Nolly map (1748)Major cities in World of Warcraft are social media that share the same positive space features. As in many real cities, positive spaces in Stormwind are formed through the rational placement of architectural figures. On the map of Stormwind it can be seen that the city has its own areas that differ from each other in the color of the roof. This is the basic and easiest way to reflect the visual identity of this another of the five Lynch forms. In addition, for more clear and visual division of space into areas in Stormwind, there are water channels, thanks to which the transition from one area to another becomes more obvious for players. Figure 8. World of Warcraft. Stormwind MapIn Stormwind, the shopping district is the site of the main concentration of social interactions between player avatars. A large number of them can be explained by the presence of such services here, which are rare in the rest of the gaming world. It's about a bank and an auction house. Positive spaces in the shopping area can be seen as a “social canvas”, where a high concentration of players increases the likelihood of their interaction. As in the case of many public spaces in a real urban environment, the high activity of the players can also be taken as a landmark for this area.

Figure 8. World of Warcraft. Stormwind MapIn Stormwind, the shopping district is the site of the main concentration of social interactions between player avatars. A large number of them can be explained by the presence of such services here, which are rare in the rest of the gaming world. It's about a bank and an auction house. Positive spaces in the shopping area can be seen as a “social canvas”, where a high concentration of players increases the likelihood of their interaction. As in the case of many public spaces in a real urban environment, the high activity of the players can also be taken as a landmark for this area. Figure 9. World of Warcraft. Stormwind Figure-Background Chart

Figure 9. World of Warcraft. Stormwind Figure-Background ChartNegative spaces in multiplayer shooters

Like the positive, negative space in urban design is determined by the spatial relationships between the architectural figures. As in the case of landmarks, game spaces can be visually identified by comparing them with the surrounding negative space. It, in turn, arises when the arrangement of the figures does not imply gaps, because of which a background, chaotic in nature, arises between them.The abnormal popularity of the Facing Worlds map from Unreal Tournament is often due to the proper use of negative space. In the case of arena shooters, negative spaces allow players to distinguish between other players - both buddies and opponents - from a greater distance. In addition, negative space helps identify game targets and massive threats. Figure 10. Unreal Tournament (1999), Facing Worlds mapLevel designer Jim Brown contrasts the rational use of negative space in Facing Worlds with its lack of Favela map in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2. Here the negative space of the outside world is difficult to distinguish from the game one, which leads to confusion, and therefore the logical discontent of the players. However, Brown insists that the design of the environment on this map only corresponds to its architectural source - the Brazilian favelas.

Figure 10. Unreal Tournament (1999), Facing Worlds mapLevel designer Jim Brown contrasts the rational use of negative space in Facing Worlds with its lack of Favela map in Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2. Here the negative space of the outside world is difficult to distinguish from the game one, which leads to confusion, and therefore the logical discontent of the players. However, Brown insists that the design of the environment on this map only corresponds to its architectural source - the Brazilian favelas. Figure 11. Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 (2009), Favela MapThe main threat to players in competitive shooters is the presence of players from the opposing team. Therefore, level designers must emphasize negative spaces in order to make the figures of players distinguishable against the background of the environment. Such an approach should reduce external factors of disappointment that are not related to the playing skills of each individual player - in this case, disappointment can come from losing by killing the enemy by hand.In Modern Warfare 2, the Takedown single-player mission also takes place in the Brazilian favel: it uses the same elements as in the case of Favela, and therefore it is characterized by the same lack of visual clarity as in its multiplayer equivalent. Level designer Dan Taylor uses this level to prove that “confusion is cool,” but admits that such an idea needs to be implemented very carefully. So it can be argued that here the absence of negative space would detract from the quality level passage to the same extent as in Facing Worlds - its presence.

Figure 11. Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 (2009), Favela MapThe main threat to players in competitive shooters is the presence of players from the opposing team. Therefore, level designers must emphasize negative spaces in order to make the figures of players distinguishable against the background of the environment. Such an approach should reduce external factors of disappointment that are not related to the playing skills of each individual player - in this case, disappointment can come from losing by killing the enemy by hand.In Modern Warfare 2, the Takedown single-player mission also takes place in the Brazilian favel: it uses the same elements as in the case of Favela, and therefore it is characterized by the same lack of visual clarity as in its multiplayer equivalent. Level designer Dan Taylor uses this level to prove that “confusion is cool,” but admits that such an idea needs to be implemented very carefully. So it can be argued that here the absence of negative space would detract from the quality level passage to the same extent as in Facing Worlds - its presence.Revision of architectural conventions for the needs of level design

Although many spatial aspects of level design are similar to their architectural sources, the ways users perceive these spaces are different. Guided by the philosophy of architect Le Corbusier regarding modern architecture, Totten argues that level design is often built around problems or other situations that must be overcome by the player: “the game level should be a machine for life, death and the creation of tension, using to achieve this all means at hand. ” To do this, some classical principles of architecture must be changed or overturned.Spatial aspects of designing a multi-user map

First introduced in Call of Duty: Black Ops, the Nuketown card was warmly received by the gaming community and has since appeared in later parts of the franchise. The popularity of Nuketown, like many other well-known multiplayer maps, can be partially explained by the skillful use of synergies between positive and negative spaces.Space organization at Nuketown is based on a typical suburban “sleeping” area. Positive and negative spaces are combined here in order to separate residential buildings and movement zones from each other. Similar solutions can be found on various university campuses. Figure 12. Call of Duty: Black Ops (2010). Nuketown Map Based on a Background PatternAlthough Nuketown-like multi-player maps correspond to the same arrangement of architectural forms as in real suburban spaces, their goals are adapted to better match the shooter genre. Nuketown's open, positive spaces are located on either side of the hedge and contain the player's starting spawn points. These areas are well protected from enemy fire. In order to meet with members of the opposing team, players must make a conscious decision to leave the safe zone provided by these spaces, in the central zone, where the lines of sight for shooting open. The vehicles on the map are used to separate this negative space.This map also has the concept of dividing space into a safe and combat zone. Some architectural decisions regarding positive and negative space are also used to identify them, where the central Nuketown area can be considered a war zone, since it is an open area that exposes the player to potential threats. The houses that occupy the largest area on the side of each team are, on the contrary, shelters, since their positive space is used to block enemy lines of sight and protect the player from shooting.The dichotomy between combat and safe areas in the design of the multiplayer level should affect the spatial experience of the player, using his survival instincts. So, players in the battlefield are probably subconsciously seeking shelter and its protection. From here, the player can once again risk venturing out into the central zone to engage in battle with enemies.

Figure 12. Call of Duty: Black Ops (2010). Nuketown Map Based on a Background PatternAlthough Nuketown-like multi-player maps correspond to the same arrangement of architectural forms as in real suburban spaces, their goals are adapted to better match the shooter genre. Nuketown's open, positive spaces are located on either side of the hedge and contain the player's starting spawn points. These areas are well protected from enemy fire. In order to meet with members of the opposing team, players must make a conscious decision to leave the safe zone provided by these spaces, in the central zone, where the lines of sight for shooting open. The vehicles on the map are used to separate this negative space.This map also has the concept of dividing space into a safe and combat zone. Some architectural decisions regarding positive and negative space are also used to identify them, where the central Nuketown area can be considered a war zone, since it is an open area that exposes the player to potential threats. The houses that occupy the largest area on the side of each team are, on the contrary, shelters, since their positive space is used to block enemy lines of sight and protect the player from shooting.The dichotomy between combat and safe areas in the design of the multiplayer level should affect the spatial experience of the player, using his survival instincts. So, players in the battlefield are probably subconsciously seeking shelter and its protection. From here, the player can once again risk venturing out into the central zone to engage in battle with enemies. Figure 13. Call of Duty: Black Ops, Nuketown map.In addition, players can use the balconies of houses to gain a height advantage over the enemy in the war zone, although this decision will require sacrificing the security provided by the house.In the end, it is worth mentioning that the size of this level is small compared to other cards used in this genre. This means that transitions between positive and negative spaces occur more often here, and therefore the frequency with which players encounter each other increases. The spirit of the place of this level can be attributed to the most intense, exciting multiplayer experience.

Figure 13. Call of Duty: Black Ops, Nuketown map.In addition, players can use the balconies of houses to gain a height advantage over the enemy in the war zone, although this decision will require sacrificing the security provided by the house.In the end, it is worth mentioning that the size of this level is small compared to other cards used in this genre. This means that transitions between positive and negative spaces occur more often here, and therefore the frequency with which players encounter each other increases. The spirit of the place of this level can be attributed to the most intense, exciting multiplayer experience.Conclusion

In architecture, from time immemorial, they have been involved in spatial theory. Over time, this philosophy defined and approved the principles of design, which today remain relevant for architects. And from our material, it becomes obvious that some of these techniques were adopted and adopted in the game level design. Where architects are guided by the goal of achieving human comfort and efficient use of space, level designers can create virtual social environments, adhering to similar rules, but achieving a different result.In addition, level developers can use the features of game genres to completely redesign the familiar theory of architecture, allowing players to experience a diverse range of emotions. From overwhelming dramatic tension to the opportunity to claim a tactical advantage over the disputed space, level designers achieve the necessary spirit of a place unique to video games. And the correct use of the relationship between positive and negative space can help create a competitive atmosphere in what would otherwise be a safe public space.Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/undefined/

All Articles